Jorge Sanguino and Alexander Herrera review on the participation costs on the new market of NFT (non-fungible-tokens) published in artishock, an specialized art magazine in Chile, follow with an article about ecological costs.a The first article is being re-published at Esfera Publica, an critic blog in Colombia. Both articles, a deep analysis on NFTs are trending in Spanish spoken countries since weeks.

Karen Paulina Biswell: Reviewed on TAZ

Karen Paulina Biswell and Aicanon participation at “Club Quarantina” on view at Grimm Musem in Berlin, curated by Gilles Neiens, was review by the german Newspaper TAZ. Written by Beate Scheder.

The exhibition open Friday the 8th, and despite the Lockdown was fully visited on scheduled.

To read the article on Karen Paulina Biswell online.

Mauricio Limon show in Madrid

Instituto Cultural de México in Spain presents Mauricio Limon. The mexican artists exhibits the “El primero que ría” The show is on view until 8th. This show product of the collaboration between the cultural institutes of Mexico in Paris, Madrid and Berlin.

Instituto Cultural de Mexico en Espana

Curated by Marcos Calderon, the show reviews Mauricios Limon´s work in the last 10 years.

Mauricio Limon @ fondation Fiminco

From the 2nd April to the 10th of April Mauricio Limon will show the body of work. Developed during his residency at Fondation Fiminco in Romanville, North of Paris.

Mauricio Limon latest woodcuts and masks are on display, along with his groundbreaking lithographic series: “se pagará a la vista del portador”.

NIKA FONTAINE in Tagesspiegel!

artcritic Birgit Rieger wrote a review on Nika Fontaine’s show “goodbye world” for the largest paper in Berlin.

“Das letzte Picknick”

Kunst und Klimakrise: Die Ausstellung „Goodbye, world“ findet auf einer Eisscholle in Schweden statt. Und geht unter, wenn es taut.

Tagesspiegel feat. Nika Fontaine‘s skull installation made of sour-dough bread in “Goodbye, World!” with Apexart.

to read more click here

NIKA FONTAINE in TAZ

“Zum Dahinschmelzen” – a review by TAZ feat. Nika Fontaine

Die Ausstellung „Goodbye, World“ von Andreas Templin und Raimar Stange bringt die Kunst ins ewige Eis. Dort geht sie dann zugrunde.

Mehrere Künstler greifen in ihren Arbeiten Motive von Nahrungsmitteln auf: Nika Fontaine ließ einen kleinen Hügel aus mit Kohle geschwärztem Schnee errichten und darauf Brotskulpturen in Totenkopfform anordnen. „Bread of Shame“, lautet der Titel. In Anlehnung an eine Lehre der Kabbala müssen das Brot der Schande diejenigen verzehren, die unverdient ein Geschenk erhalten haben. Gängigen Auslegungen zufolge ist dieses das Geschenk des Lebens, woraus sich die individuelle Verpflichtung ergibt, dieses sinnvoll zu gestalten.

TAZ 3/16/2021 by Andreas Schlaegel

to read the full article click here

NIKA FONTAINE review in 4 Columns!

An excellent review by Ania Szremski on the exhibition and Nika Fontaine work at 4 columns: “Goodbye, World”. On thinning ice: an environmental anti-memorial in Sweden .

4 Columns feat Nika Fontaine

The story of creating this exhibition and the resulting images of this magnificent frozen world, the spine-tingling sublimity of its vast bleached expanse, which so few people will ever get to see, are all so spectacular, it’s perhaps inevitable that they would overshadow the artworks themselves. Some of them are wholeheartedly forthright interpretations of the theme. For instance, Montreal-born, Berlin-based artist Nika Fontaine offered a mound of active charcoal, like an extinguished funeral pyre, studded with cartoonish human skulls formed out of bread, with smoke wafting from burning frankincense. “It is only fair of you [Earth] to put an end to our selfishness . . . I welcome your wrath as an act of self-care and preservation,” Fontaine writes in an accompanying letter. There’s also Berlin-based Veit Schütz’s Aggregat Weltenbrand (Aggregate World in Flames) (2017), an old-fashioned, lacquered wooden radio equipped with a glowing 3D print of the planet Earth. In the original iteration of the artwork, the viewer could depress a red button to ignite a series of explosions across the miniature world. (A GIF on the exhibition website shows what this looks like, but the actual work installed on the ice floe is an “environmentally friendly” copy, sans electronics.)

by Ania Szremski, 2/19/2021

for the full article click here

NIKA FONTAINE in ArtMagazin

“Eisbär’n müssen doch weinen”, in ArtMagazin 17.02.21

Nein, es ist nichts mehr klar wie im Text zum Song „Eisbär“ der Schweizer Band Grauzone aus dem Jahr 1980. Schon damals gab es besorgte Stimmen, die vor einem globalen Temperaturanstieg und den damit verbundenen Problemen warnten. Jetzt, 40 Jahre später, sind die Auswirkungen eines ungezügelten Kapitalismus weltweit spürbar. Wetterkapriolen wie der kürzliche Wintereinbruch in Norddeutschland und immer neue Temperaturrekorde haben endlich eine gesellschaftliche Diskussion um nötige Gegenmaßnahmen angefacht, in der auch die Kunst eine zunehmend wichtige Rolle spielt.

artmagazine-Autor Raimar Stange hat bereits im Jahr 2020 die Ausstellung „2050 Nature Morte – Kunst zum Klimawandel“ in Berlin kuratiert. Nun hat er sich gemeinsam mit dem Künstler Andreas Templin für Goodbye, World eine radikalere und auch endgültigere Ausstellungssituation als die üblichen White Cubes gesucht. In den eisigen Weiten des Bottnischen Meerbusens in Nordschweden inszenierten die beiden eine finale Ausstellung zur Verabschiedung der Welt, wie wir sie kennen. Locker verteilt auf der Eisfläche erweisen die Werke von 10 Künstler*innen der Erde vor dem Klimakollaps noch eine letzte Reverenz.

Mit einer Opfergabe von Brot und Wein entlässt Nika Fontaine die Natur in eine neue, unentdeckte Zukunft, die vielleicht frei sein wird von der Raffgier der menschlichen Zivilisation. Olaf Nicolai lädt zu einem letzten opulenten Picknick auf dem Eis, bevor die steigenden Temperaturen alles im Meer versinken lassen.

Mit der fortschreitenden Klimakrise werden technokratische Allmachtsfantasien ad absurdum geführt. Nicht die Ausweitung der Technologie, sondern die Rückbesinnung auf lang tradierte Praktiken vom achtsamen Umgang mit der Natur können uns allenfalls noch davor bewahren, die volle Wucht der Veränderungen zu spüren zu bekommen.

To read the full article click here

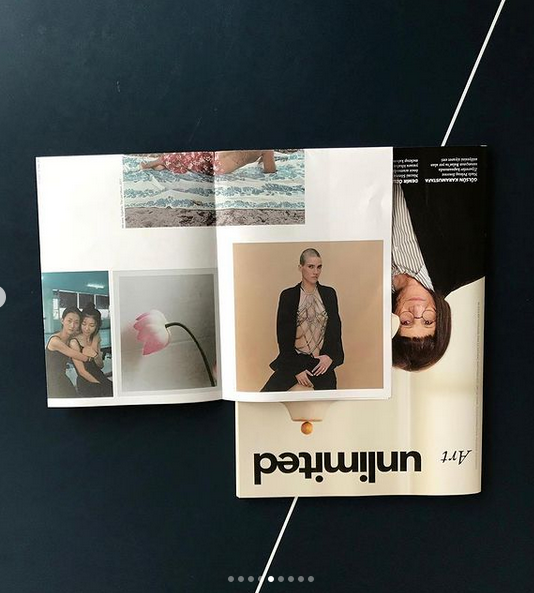

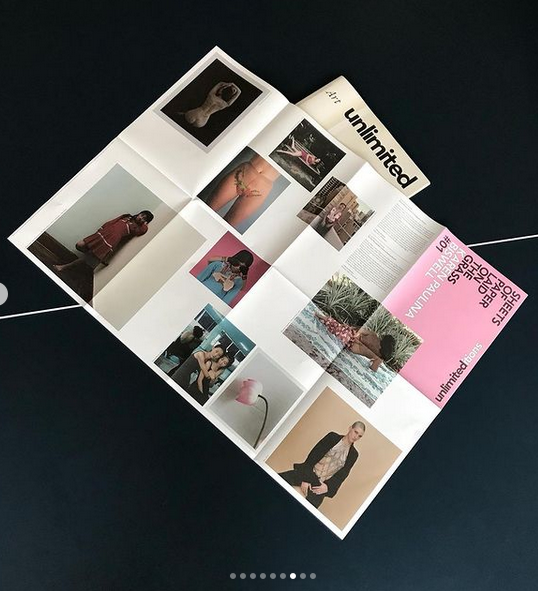

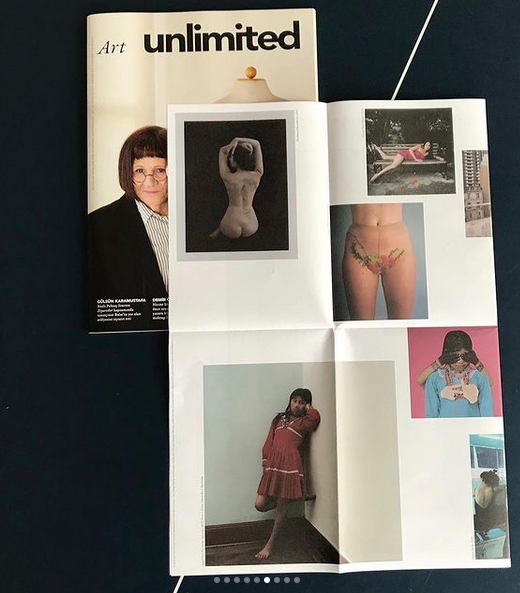

KAREN PAULINA BISWELL special in Art Unlimited Magazine

New Insert Project in https://www.unlimitedrag.com/art-unlimited

SHEETS OF PAPER LAID ON THE GRASS

#01 Karen Paulina Biswell

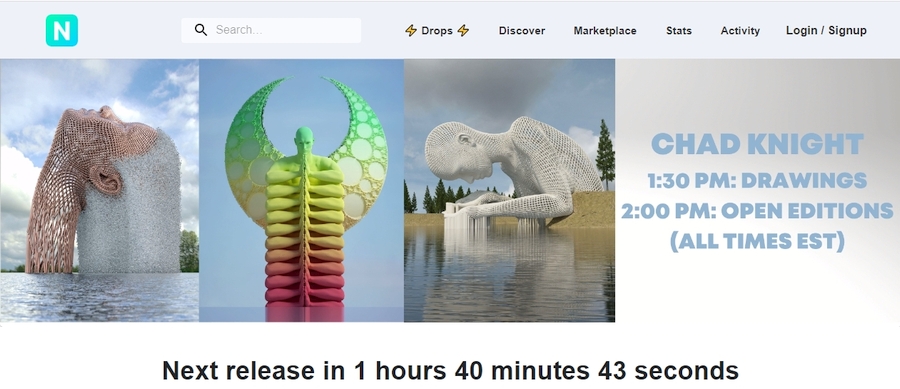

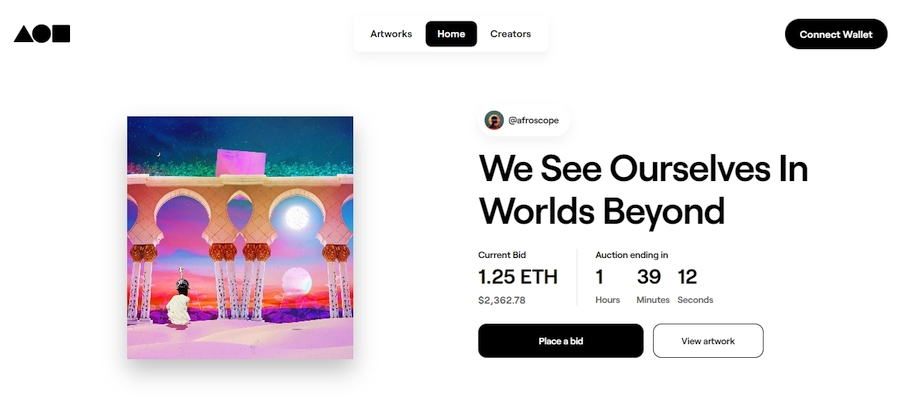

“EL MERCADO DE ARTE DE LOS NFTs” New article by Jorge Sanguino in Artishock!

EL MERCADO DE ARTE DE LOS NFTs. LOS COSTOS REALES MÁS ALLÁ DE LOS GATOS Y LOS UNICORNIOS

by Jorge Sanguino & Alexander Herrera Sotomonte

published 3/14/2021 on Artishock Revista

La venta de medio millón de dólares del gif del gato Nyan en el nuevo mercado de arte NFT, sumada a la participación de Christie’s en este nuevo mercado de arte, a través de la subasta con Beeple, ha sido registrada por casi toda la prensa, no sólo la especializada en el mercado de arte, sino la prensa en general. De seguro la mayoría de los lectores ya tienen una idea de este nuevo mercado del arte (por el momento, arte digital), que funciona utilizando la tecnología Blockchain.

En pocas palabras, los artículos de prensa y televisión reportan la aparición de nuevas plataformas para la compra y venta de arte, en los que la imagen, el video, el sonido o simplemente el code de programación, a decir, la obra de arte, se revierten en un nuevo medio: los NFTs (non-fungible tokens). El token enlaza la imagen, sonido, video, etc con una cripto moneda (en la mayoría de los casos, ethereum) “registrándolo” en el blockchain. De esa manera, la obra de arte, a la que llamaremos NFTs, adquiere la garantía de la univocidad, y comienza a participar de una dinámica de transacciones muy específica y con características propias que ya tendremos ocasión de revisar.

Recordemos que estamos hablando de un nuevo mercado de arte, y no de un movimiento estético, por lo que su naturaleza contemporánea consiste en ofrecerse como lugar para transacciones mercantiles, compra y venta, donde se reúne el vendedor con el comprador. Bajo este aspecto, el mercado de arte NFTs ofrece a través de sus propiedades específicas soluciones a problemas del mercado de arte tal y como lo conocemos, es decir, el mercado de arte clásico. Con el lanzamiento de los cryptopunks en junio del 2017 se inició este nuevo mercado de arte que comienza a originar millones en la medida que la forma de pago incrementa su valor exponencialmente. Hoy, plataformas como SuperRare o Nifty Gateway compiten unas con otras, haciendo lanzamientos cada dos días de nuevas obras de los artistas digitales.

Para empezar, el mercado de las NFTs, soluciona el problema de la originalidad de la obra de arte y el de su univocidad, concediendo un certificado incorruptible en la blockchain y seguro contra las falsificaciones. Pero más allá, la tecnología mencionada origina la certeza de que el número de series de una pieza de arte (cuya naturaleza es la de ser reproducible, como las artes gráficas, la fotografía, el video, el arte sonoro y el arte digital), tiene el respaldo de un sistema de correlación y de comprobación. Como sabemos, anteriormente, únicamente disponíamos de la palabra del galerista, del merchante y del artista, que garantizaban que el número exacto de series correspondían con la del número de obras que habitan el mundo.

La certeza de que la pieza que se posee es la única, o parte de una serie restringida, es un problema que originó el mercado de arte clásico, pues la numeración exacta afecta el valor de la pieza. Un número pequeño y conciso incrementa su particularidad y, por tanto, el precio. Curiosamente, en el campo de las artes visuales la necesidad de consolidar un valor es contraria a los mecanismos necesarios para la distribución de una imagen. Pues, históricamente, la reproducción de una obra de arte por medios gráficos era parte de las prácticas de los grandes artistas del renacimiento, que valoraban una recepción amplia de sus obras por medio de la circulación de grabados. De igual forma, para los fotógrafos era más importante la circulación de su imagen a través de las oficinas de prensa, que originar un número exclusivo de ella. Sin embargo, a partir de los años setenta, con la entrada de la fotografía al mercado del arte, las condiciones de la distribución de la imagen cambian.

De igual forma, el mercado del arte clásico ha gravitado en torno de una disputa del original y de la copia, disputa en que el original debidamente autentificado con la firma del artista y los sellos de proveniencia sirven de garantía de que la obra de arte interviene en la esfera del asset. Es preciso observar que esta especie de compulsión referida a la determinación de la originalidad de las piezas de arte, no sólo ha creado sistemas complejos de autenticidad y veracidad, como los famosos catalogues raisonnés (en muchas ocasiones amañados a los intereses de sus editores, en su mayoría marchantes del arte, en los que incluyen y excluyen obras según los beneficios financieros), sino que a su vez ha dado lugar a la figura del copista hábil, que logra imitaciones al estilo del artista famoso, y de esa manera puede inundar el mercado de arte con nuevas obras que el artista nunca produjo.

Otro problema que el mercado de arte NFTs soluciona es el de la participación directa del creador en el mercado, evitando intermediarios. El creador puede acceder desde su computador a la plataforma, y ofrecer su obra directa a los compradores. Como bien sabemos, el mercado del arte clásico está formado por los llamados market makers, que en los últimos años no sólo es un ejercicio de las galerías, sino además concierne a coleccionistas y curadores. La participación directa del artista soluciona además el problema del pago de royalties, o comisiones, que se originan una vez la obra es revendida. El creador puede decir durante el proceso de minting, o el momento en el que la obra de arte es enlazada en el Blockchain, qué porcentaje recibe él por las futuras postventas, así como decidir el porcentaje que reciben los colaboradores. En el mercado del arte clásico persiste la constante batalla por el derecho a especular sobre el valor de una obra (con esto afirmo que no se trata de evitar la especulación, sino del “derecho” a especular con el valor).

Cuando un artista tiene una demanda alta los galeristas ejercen control sobre el número de obras disponibles, y tácitamente buscan que el comprador no revenda la obra antes de diez años, evitando que el comprador haga una ganancia jugosa, más otorgándose a sí mismos el derecho de especular. Muchos coleccionistas declaran, antes de preguntar por el precio, su “amor incondicional” por el arte, y tratan de ganar créditos a través de compras que serán prestadas (desde hace unos años nadie habla de donaciones) a los museos. Las famosas listas de espera, así como las listas negras, hacen parte del mundo del arte.

En este momento el estado del mercado de arte NFT es incipiente. Las obras son productos de diseñadores o creadores digitales. En el momento la mayoría de las obras que circulan son creadas por diseñadores, animadores, y creadores de video juegos. Gifs de gatos íconos en la cultura del internet, como el Nyan Cat, alcanzan precios de medio millón de dólares. Otros memes que circulaban desde hace décadas sin tener propietario, ahora reclaman una autoría y un costo para su posesión. Sin embargo, este estado puede cambiar rápidamente. Como era de esperarse, ya artistas bluechip, como Damien Hirst, anunciaron que querían participar en el nuevo mercado. De esa manera, se incrementa el riesgo de quela estrategia de la especulación y la creación de precios inflados, también se aplique dentro del mercado NFTs, creando transacciones de compra y venta con el fin de aumentar el valor de una pieza artificialmente. Aquí las transacciones pueden ser ficticias, no porque el dinero no se deposite de una cuenta a otra, sino porque el vendedor y comprador pueden ser la misma persona con diferentes wallets.

Ya sabemos que el incremento inflado y especulativo del valor de una obra de arte afecta el juicio estético. Más en el mundo digital, al incrementar el valor, la pieza sube al ranking de lo más vendido, haciendo que el artista también mejore sus posiciones en el ranking, por consiguiente, siendo más visible que los demás. Sin duda, de esa manera los especuladores profesionales del arte van a participar en el mercado NFTs, que por cierto, aparece en el momento más propicio, porque en él es posible continuar con las prácticas de lavados de activos y evasión fiscal que comienzan a ser controladas en el mercado de arte, y que han obligado a las galerías y los comerciantes de arte a ajustarse a nuevas directivas en ambos lados del Atlántico.

La ideología de democracia del mercado de NFTs, sin embargo, plantea dos preguntas. 1. ¿Cuál es el costo de participación en el mercado?, y 2. ¿Quiénes pueden estar excluidos de éste por las condiciones que tiene, y cuáles son las soluciones? Aquí queremos señalar críticamente el rol que juega el mercado en la fabricación de juicios estéticos, los que dan paso a la creación de canon dela historia del arte contemporánea.

La primera condición para participar en alguna de las plataformas de mercado NFTs (SuperRare, Nifty Gateway, o Foundation.app) consiste en tener una wallet (billetera) donde se deposita la criptomoneda, y que sirve además como identificación. Para ello, no es necesario comprar ninguna fracción de una criptomoneda, que por su valor especulativo resulta bastante costosa de adquirir en las economías de los países no desarrollados, sobre todo aquellos que padecen procesos de devaluación. Y aunque en primera instancia estaríamos hablando de un costo inicial bastante bajo, sin embargo, un análisis más detallado de los costos de participación del mercado, no de un sólo individuo sino de un grupo social, digamos artistas latinoamericanos, comienza a cambiar la hoja del balance.

El primer costo importante que es preciso considerar, consiste en los procesos de capacitación que exige desenvolverse en un nuevo mercado, entendiendo el set de reglas que le son intrínsecos. Si una nueva generación de artistas quiere participar en el mercado NFT, ello implica producir y distribuir el conocimiento referido a estos asuntos, más allá del consumo de noticias. Un segundo rubro lo imprimen los costos para la adquisición de hardware con capacidad computacional suficiente destinado a la constante producción de las obras de arte, así como la vigilancia de sus transacciones dentro del blockchain, sumado al software de producción digital, de uso a través de suscripción de precio bastante elevado.

Estos costos resultan altos porque son prácticamente estables en todo el mundo, y no se acomodan a la capacidad adquisitiva de un país en particular, por ejemplo, ajustándose al sueldo mínimo o los costos reales de la canasta familiar. Pero, además, en muchos países en vías de desarrollo (también en regiones sacudidas por catástrofes naturales, climáticas-medioambientales, humanitarias, consecuencia, por ejemplo, de conflictos bélicos) la falta de una infraestructura adecuada para el acceso a Internet, así como de una infraestructura de seguridad contra ataques de hackers, son parte importante de los desafíos que enfrenta la oferta artística de estos países referidos a su participación en el mercado de los NFTs. En este sentido, los miembros y colectivos de centros rurales y de las comunidades indígenas se encontrarían prácticamente excluidos de participar directamente de este mercado, e incluso de relacionarse con las tecnologías informáticas. Y aunque países con bajos recursos como Irán o Corea del Norte han desarrollado sofisticados equipos de defensa cibernética y han adelantado incluso ataques, no es común que otros países con economías similares destinen recursos a este rubro, de manera que sus infraestructuras resultan vulnerables a los ataques dirigidos al robo, fraude o engaño con la criptomoneda.

Otro costo que es preciso tener en cuenta, tiene que ver con las limitaciones de la banca nacional en estas economías, un sector bancario que posiblemente no puede competir con otras estructuras similares de países industrializados, porque no disponen de la capacidad ni tienen la necesidad -por el momento- de ofrecer la transferibilidad o convertibilidad, es decir, la posibilidad de que la criptomoneda sea transferida del mundo digital al mundo de las divisas convencionales. En este orden de ideas, el balance que tiene en cuenta el índice de costos y los problemas técnicos, permite anticipar que gran parte de la oferta creativa de Latinoamérica podría quedar excluida de la participación en el mercado NFT, asunto que tendría como efecto adicional, un poco inesperado, una posible homogenización de sus contenidos y de sus formas, una especie de parálisis por falta de competitividad, de actualidad.

Alexander Herrera Sotomonte (Venezuela) es Filósofo por la Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá. Vive y trabaja en Colombia y se ha especializado en las TIC (Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación) y en la divulgación de tecnologías de información en los segmentos de la sociedad que no tienen acceso a los medios.

Jorge Sanguino (Colombia) es Filósofo por la Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá, e Historiador del Arte por la Humboldt de Berlín. Cofundador de wildpalms, en Düsseldorf, una plataforma con énfasis en investigación artística, prácticas sociales y medioambiente de artistas latinoamericanos en Alemania.