Precarization and Self-precarization

2020/08/01

By Jorge Sanguino

ENGLISH VERSION

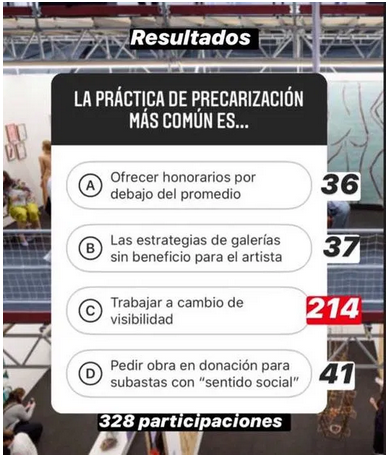

With great interest I read the post by William Contreras in Public Sphere, which afflicts and rightly criticizes the practices of labor abuse within the cultural industries. In a series of questions on Instagram that Esfera Publica asked the audience, the participants described situations in which precariousness occurs. The majority considered that the exchange of work for “visibility” was the situation most within the cultural industry.

For a few years I have analyzed the issue of precariousness in the cultural industry, and I strongly agree that, wages below what is legally established, the “evasion” of labor agreements that guarantee the safety of an employee, and the areas grays in relation to work-remuneration-leisure have originated a concentration of wealth for some actors. In some cases they are art dealers, in others they are collectors, but so are artists and, surprise!, Curators. The morality of the art world, which is really a mustache, was pulling its hair out when three years ago it was discovered that the curator of the Stedelijk museum in Amsterdam, Beatrix Ruf, had an art consulting company in Switzerland that was increasing her salary official, paid with the taxes of the citizens of the Netherlands, a couple of zeros on the right side. As the director of a museum, financed also with public money, she could favor the collectors she advised, exhibiting her pieces inside the museum, or warn them which young artist was going to be exhibited in the next few years.

The creation of wealth through labor abuse within the cultural industries is, however, more complex than it seems. We have to understand that together with the increase in economic value (of a piece of art, for example), and together with the increase in earnings through labor abuse or breaking of social agreements, is the increase in cultural value, which is subject to monopoly, which creates wealth within the industry.

In the precarious experiences compiled by Esfera Pública on Instagram, their tenor described the repeated disappointment of the gallery that does not pay the artist, of the money that does not appear, of the artist’s costs that are not covered, and the exchange of work for visibility. My interest in the processes of precarization in culture have been focused on finding what is systematic in cultural industries, and sometimes I prefer to change the term of “precarization” for that of “extraction” and “monopoly”. The reason is the following, despite the tragedy and anger that most of the situations described involve, they do not appear exceptionally within the world of art, but are found in all commercial activity between individuals. For example, the lawyer who charges and does not move the process, the engineer who does not respond for the wrongly calculated work, etc., etc. and each one will know an example. And most of them can be dealt with through artist contracts, a work loan contract, and an equitable sharing of costs.

An art commentator once wrote that everyone talks about prices at art fairs, because talking about money is easier than talking about art. However, the opposite appears to be true within the cultural industries. Everyone talks about art and nobody talks about money. A common denominator of the experiences compiled by Esfera Pública is that they are lived by artists, and they leave a rather bitter aftertaste, but also a concern. It is necessary to extend within the artistic community and cultural workers, a basic management education. This implies knowing how to calculate the costs of living, social security, labor costs, etc., in addition to knowing the tax regulations, and the effects they can cause to commercial activity, and contracts with which a healthy commercial relationship is established. A series of questions appear: Do I want to exhibit in a place where it would barely cover production costs? But, don’t be surprised, this same question can be asked from the other perspective: Do I want to do an exhibition if it does not cover the monthly costs of the gallery? Otherwise, do I want to exhibit in a gallery without a commission contract or loan of works of art? And in the opposite version: do I want to exhibit and invest in the career of an artist who without a contract will be selling directly in his workshop without participation to the gallery?

Certainly the artist and cultural workers embody the dream of neo-capitalism: flexible and independent workers who take their own risk. Furthermore, a basic education in administration, dedicated as we are to establish commercial relations based on cultural objects, is the only way to find a language and solidary solutions in the face of “extraction and monopoly processes”, that is to say, precariousness.

A common language as a means of collective resistance offers a possibility to lessen one of the negative effects of extraction and monopoly processes in the future. The one of exclusion. In the current labor and education situation, only those who have the external economic resources to continue with self-precarization, and sustain it for a long term, can be artists and cultural workers. Most may be members of wealthy families, or beneficiaries of direct assets, or those who decide to go into debt with banks, as has happened with art students in the United States. Changing the present of labor relations within the cultural world has a direct implication for the future.

by Jorge Sanguino